Strings in C

Unlike many higher-level programming languages, C does not feature an explicit string type. While C does allow string literals, strings in C are strictly represented as character arrays terminated with a null byte (\0 or NUL).

In C, strings are a special case of character arrays; not all character arrays are considered strings, but any contiguous and null-terminated buffer of characters is guaranteed to behave like a string.

We can declare and initialize strings a few ways:

char* s = "CS@UIUC"; // Set a char pointer to point to string literal in read-only memory

char s2[8] = "CS@UIUC"; // Initialize a char array on the stack using a string literal

char s3[8] = {'C','S','@','U','I','U','C','\0'}; // Initialize a char array on the stack using an array literal

char* s4 = malloc(8); // Dynamically allocate memory for a string then write a string literal to that memory

strcpy(s4, "CS@UIUC");

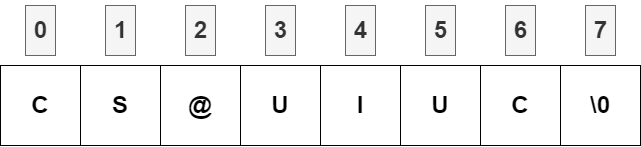

char* s5 = strdup("CS@UIUC"); // Same as using malloc and strcpyRegardless of how our string is initialized, the way that our string is represented in memory will look like this:

Some important string stdlib functions

The C standard library implements a number of functions for operations on strings in string.h. Here, we'll give a brief overview of the most important functions.

Comparison and length - strcmp, and strncmp

int strcmp(const char *s1, const char *s2);

int strncmp(const char *s1, const char *s2, size_t n);

int strlen(const char *s);

strlen will count the number of characters in s until it reaches the null byte. Put more simply, it will return the length of any string.

printf("%d", strlen("ABCDEFG"));7

strcmp is C's string comparison function. Provided two strings s1 and s2, strcmp will return 0 if s1 and s2 are the same, 1 if s1 is greater than s2, and -1 if s2 is greater than s1. Note that computing which string is "greater" is done by comparing the ASCII codepoints of the characters in the string one by one, so strcmp can be used as a case-sensitive lexicographic comparison.

strncmp performs roughly the same function. Given s1, s2 and some integer n, strncmp will compare the first n bytes of each string.

int c1 = strcmp("A", "A");

int c2 = strcmp("AB", "BA");

int c3 = strcmp("BA", "AB");

printf("%d\n", c1);

printf("%d\n", c2);

printf("%d\n", c3);0 -1 1

Concatenation - strcat and strncat

char *strcat(char *dest, const char *src);

char *strncat(char *dest, const char *src, size_t n);

Given two strings src and dest, strcat will concatenate src onto dest. strcat will also handle null bytes, removing the null byte of dest and adding a null byte to the end of the concatenated string.

char c[24] = "I love ";

strcat(c, "systems!");

printf("%s", c);I love systems!

Like strncmp, strncat performs about the same function as strcat, but only concatenates the first n bytes of src onto dest.

Search functions - strchr, strrchr, and strstr

char *strchr(const char *s, int c);

char *strrchr(const char *s, int c);

char *strstr(const char *haystack, const char *needle);

Given a string s and some character c, strchr will search for the first instance of c in s and return a pointer to that instance. If there is no instance of c in s, strchr will return a null pointer. strrchr is similar, but will instead search for the last instance of c in s.

char s[8] = "ABCDEFG";

char* c = strchr(s, 'B');

printf("%p", c); // This will print an arbitrary memory address, depending on where 'B' is allocated.

printf("%c", *c);0xbfb7c860 B

strstr will attempt to find an instance of a substring instead of a character. Given two strings haystack and needle, strstr will return a pointer to the first character of the first occurrence of needle in haystack. Like strchr, strstr will return a null pointer if needle cannot be found.

char s[8] = "ABCDEFG";

char* c = strstr(s, "ABC");

printf("%c,%c,%c", *c, *(c + 1), *(c + 2));A,B,C

Copying and allocating strings - strcpy, strncpy and strdup

char *strcpy(char *dest, const char *src);

char *strncpy(char *dest, const char *src, size_t n);

char *strdup(const char *s);

Given two character arrays dest and src, strcpy will copy the contents of src into dest character by character, stopping when it reaches a null byte (note that strcpy will also insert a terminating null byte).

strncpy is roughly equivalent to strcpy, but will stop copying from src into dest either when it has copied n characters or when it reaches a null byte, depending on which comes first. It is important to note that if strncpy does not reach the null byte before copying n characters, then it will not insert the null byte into the character array it is copying into.

By contrast, strdup will create a duplicate of some string s, allocate memory for that duplicate, and return a pointer pointing to the first character of the duplicate. In practice, using strdup is equivalent to malloc'ing the required amount of memory for a string and then copying that string using strcpy. As with anything that is malloc'ed, the duplicated string should be deallocated with free to avoid memory leaks.

// These are equivalent!

// 1.

char* c1 = malloc(4);

strcpy(c, "ABC");

// 2.

char* c2 = strdup("ABC");

printf("%s", c1);

printf("%s", c2);ABC ABC

Tokenization - strtok and strtok_r

char *strtok(char *restrict s, const char *restrict delim);

char *strtok_r(char *str, const char *delim, char **saveptr);

strtok and strtok_r are C's string tokenization functions. These are significantly more elaborate in specification and implementation than the rest of the functions mentioned here, so we've made a separate article covering how they work. You can find the article here.

Common pitfalls

Forgetting the NUL byte

If a string features no terminating null byte, most of the string functions we covered earlier can break entirely! For example, since strlen counts the number of characters prior to the null byte in a string, it can overcount if no null byte is provided.

// This snippet can cause undefined behavior!

char* s = malloc(2);

s[0] = 'A';

s[1] = 'B';

int i = strlen(s); // Could be 2, could be higherIt's also important to make note that strings must be strictly null-terminated, meaning that a string should not contain a null byte in any position besides the last position. In practical terms, including a null byte in a non-terminal position will also cause our standard library functions to break. Consider the following example:

char* s = "This is\0 a test!";

printf("%s", s);This is

In this case, printf exited early! The since the specification of our print format tells the function to print until it reaches a null byte, all of the string after the null byte we added will never get printed.

Buffer overflows

It is important to note that the functions in C's standard library do not do any boundary checking at runtime to ensure that array operations are only occurring within the range of memory that is allocated to them. So, it's possible to cause a buffer overflow, where a program writes data to memory outside of the range that is allocated for a particular buffer or array it is operating on.

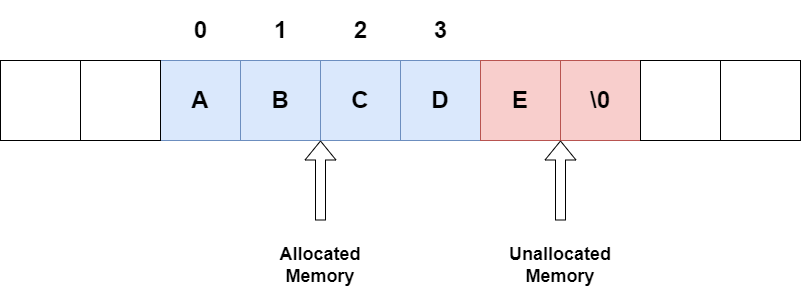

In C, buffer overflows from strings are typically the result of misuse of standard library functions. For example, buffer overflows occur when strcpy or strcat are used on under-allocated strings. Consider the following example:

char* s1 = malloc(4); // Not enough memory for 'E' or the null byte!

strcpy(s1, "ABCDE");

printf("%s", s1);The memory model for this allocated string will look like this:

Obviously, we've written past the bounds of our string! The practical effect of a buffer overflow is that we can overwrite other data that is sits adjacent in memory to our string. This is the basis of a buffer overflow attack, which is a possible vector to attack a certain program maliciously. You can read more about buffer overflow attacks here.

Changing read-only memory

As we briefly discussed at the beginning, assigning a character pointer to a string literal makes that pointer point to a string that exists in read-only memory, meaning that any attempts to modify that string will cause a program to segfault. Let's consider the following example:

// We can do this a few ways...

// This works...

char s[] = "Go systems!";

s[0] = 'T';

// This works...

char* s2 = malloc(16);

strcpy(s2, "Go systems!");

s2[0] = 'T';

// This doesn't...

char* s3 = "Go systems!";

s3[0] = 'T'; // This will cause the program to segfault!Segmentation Fault

As a rule of thumb, fixed-size modifiable strings should usually be initialized directly as arrays instead of pointers. Any dynamically-sized modifiable strings should be allocated with malloc.

Further Reading

From the Systems Encyclopedia:

Outside readings:

- string(3) - Linux manual page